Good Fire: The Case for Cultural and Prescribed Burns

With the support of science and state law, good fire can help mitigate megafires—an increasing threat for Indigenous and rural Californians

- By Kate Gonzales

- Conservation

- Sep 24, 2025

Steven Saiz, a member of the Hoopa Valley Tribe, throws flames from his drip torch during a 2023 cultural burn along the Klamath River. (Photo by Maddy Rifka)

JUST A QUARTER ACRE IN SIZE, a thicket of bear clover 60 miles northwest of Yosemite National Park amounts to a small patch of rural land. But it reflects a major shift.

About two dozen people convened in April to set this site ablaze in the Sierra Nevada town of Twain Harte, California—including kids absorbing lessons on fire safety and a man who brought along neighbors eager to learn more about “good fire” after seeing him use it on his own property.

Susie Kocher, forester and natural resources advisor for the University of California Cooperative Extension Central Sierra, helped lead the demonstration in Tuolumne County. With 25 to 50 of these prescribed burns under her belt, it may have been the smallest burn she has participated in, but “I’m not necessarily always trying to produce a lot of acres,” she says. “I’m trying to produce a lot of informed landowners.”

So-called good fire—the intentional use of fire for beneficial ecological, land-management or cultural outcomes—is gaining momentum, increasingly recognized as a tool to limit destructive wildfires in rural California and in grasslands, shrublands and even some wetlands across the country, from the Great Plains to the Southeast.

“The antidote to trauma is agency,” says Benjamin Cossel, a public affairs officer with Stanislaus National Forest who, in his off-hours, volunteers on the Tuolumne Prescribed Burn Association steering committee, which organized the burn. “As a citizenry, Californians are pretty damn traumatized.”

In recent years, California has seen a dramatic rise in megafires, or those that reach 100,000 acres or more. Reuters reported that 70 percent of the largest wildfires in state history had occurred since 2020—the year megafires destroyed 2.5 million acres, and 4.3 million acres in the state burned overall. With the spread of invasive species, and climate change causing uneven precipitation and longer periods of heat and drought, more wildfires are burning larger and hotter.

The trend has been lethal—including the 2018 Camp Fire that tore through Paradise and surrounding towns, making it the deadliest fire in state history, with 85 people killed—and is now impacting cities. This year began with fires in and around Los Angeles that grew into some of the state’s most destructive, resulting in 31 deaths and more than 16,000 homes and structures burned. Beyond the tragic loss of life, wildfires cause ecological harm, from altering the flight paths of migratory birds to the degradation and destruction of landscape-scale habitat.

But a growing movement of Indigenous groups, fire professionals, landowners and educators contends that the application of good fire helps offset environmental risks—including runaway megafires—and protects human communities. Together, they have pushed for recent laws in California permitting beneficial burns, facilitating good-fire education and fostering an exchange of trust between Indigenous groups and government agencies that has led to an about-face in state and federal practices. Advocates see the work as meeting the moment in rural California and throughout the United States.

“The Forest Service is just one piece of the puzzle,” Cossel told the Twain Harte crowd. “CAL FIRE (the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection) is one piece of the puzzle. And this,” he said, gesturing to the group of all ages gathered amid the shrub, “is the rest of it.”

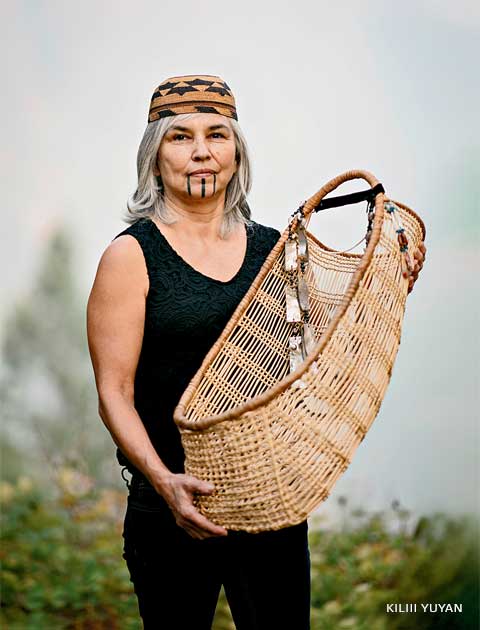

Margo Robbins (pictured) presents a cap and basket woven from hazel, a native plant aided by fire. A Yurok-conducted fire killed a fir sapling in Northern California (below) that would have competed with beneficial oaks.

A mixed history of support

For millennia, Indigenous Peoples used fire to alter the landscape for ceremonial, ecological and utilitarian ends—practices today known as “cultural burns” to differentiate them from “prescribed burns,” or fires without Indigenous ties.

Margo Robbins, an enrolled member of the Yurok Tribe, co-founded what is now the Cultural Fire Management Council (CFMC) after her community prioritized bringing fire back to their forested region of Northern California. Like others, Robbins was motivated by the desire to see her grandchildren carried in traditional Yurok baskets woven from hazel, a native shrub aided by fire. Burning a hazel patch reduces brush, lessening competition for sun, water and nutrients; manages invasive plants; and provides a clearer path come harvest time. Fire also helps produce hazel rods that are straight, strong and flexible for weaving. After educating themselves on relevant laws, the group conducted its first burn in a traditional hazel foraging spot in 2012, helping kick off a resurgence of basket weaving among the Yurok who reside along the Klamath River.

“Since then, my purpose has been greatly expanded,” Robbins says. “As I learned more and more about fire, I came to learn that the health of the land is closely, closely, closely tied with the health of our people.” Today the group coordinates planned burns with regional partners; tracks the effects of good fire on plants, from native grasses and five varieties of California Indian potatoes to invasives like Himalayan blackberry and French broom; and loans equipment, helps prepare land and provides day-of burn support to families who live within Yurok Reservation boundaries, whether they’re Indigenous or not. Last year CFMC supported 10 family burns and held 24 prescribed burns with cultural objectives.

Vikki Preston, a member of the Karuk Tribe, lives upriver from Robbins in the town of Orleans. As a technician with the Tribe’s Department of Natural Resources, she preserves archaeological artifacts and cultural resources—work that connects to her own basket weaving and fire use.

“You’re burning with cultural values in mind, and those values are not just fire values; they’re ecosystems values, ceremonial values, community values,” Preston says, linking fire to gathering, hunting and sacred ceremonies. Cultural burns often reinforce sovereignty rites and group-specific customs, such as beginning fires with wormwood torches and prayer.

But cultural burning has not seen consistent support in the United States. As a means of stifling Indigenous culture, California’s 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of Indians was among the first state laws to prohibit cultural burning. In the years that followed, rangers reportedly shot people they found conducting cultural burns. Into this century, authorities smothered cultural and prescribed burns rather than encouraging them. The 1911 Weeks Act effectively outlawed both practices, allowing brush to build up to hazardous levels and dramatically altering the ecology of American forests.

Whereas “fire suppression” is intended to manage the spread of wildfire, agencies including CAL FIRE and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) operated from an ethos of “fire exclusion,” says Lenya Quinn-Davidson, director of the Fire Network for University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. She distinguishes the two as follows: “Fire suppression is an act; fire exclusion is a philosophy.”

“That exclusion of fire across the landscape has created some of the forest health concerns we have here today,” says Joe Tyler, director of CAL FIRE, in an April webinar. Factor in a history of aggressive logging nationwide—the removal of large, fire-tolerant trees, in particular—and settler livestock grazing, and North American forests today are in rough shape. “We recognize we can’t do this alone, and we recognize that we can’t respond our way out of this,” Tyler says.

In 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom issued an apology to all Indigenous People in California for the state’s genocidal origins—an outreach that served as a jumping-off point for State Senate Bill 310, legalizing cultural burns and co-sponsored by the Karuk Tribe, that went into effect January 1, 2025. In March, Newsom’s California Wildfire & Forest Resilience Task Force issued priorities for the year, including expanding cultural burns and establishing a prescribed fire training center. In April, Newsom allocated over $170 million for forest and vegetation management and wildfire response and resiliency.

“We’ve worked with state agencies for 8 to 10 years to try to overcome these historical wrongs,” says Bill Tripp, director of natural resources and environmental policy with the Karuk Tribe. He calls the state bill “the first real, solid step towards us ... having Tribal, federal, state, local and even private citizen coordination, which is really exciting.”

As state and regional leaders reckon with increasing megafires, more agencies are turning to the Indigenous lessons of controlled burns. Even USFS mascot Smokey Bear’s former tagline, “Only you can prevent forest fires,” has been adjusted to distance the service from its past approach. “Smokey Bear’s message … should not be conflated with wildfire management practices both past and present,” the USFS website read until early August of this year. (See the “Central Key Messaging for Smokey Bear” tab on an Internet Archive version of the page; similar sentiment still exists, for now, in a USFS post from 2023.)

Today CAL FIRE, USFS and the Bureau of Land Management have begun to support planned burns for forest stewardship and cultural purposes. In its first burn 13 years ago, CFMC partnered with CAL FIRE in what is now a common hybrid model: a prescribed fire with cultural objectives.

“Our culture is fire dependent,” Robbins says. “When they come to burn with us, it’s a lot more than just reducing hazardous fuels. It is enabling us to carry on our traditional life ways.”

Robbins (pictured) leads others in lighting bundles of wormwood—a ceremonial start to a cultural burn near Weitchpec, California. A burn near the town of Orleans (below) reduces potential wildfire fuel on the forest floor.

The ecology of exclusion versus planned burns

Those long years of fire exclusion continue to impact California ecologies today. While climate change has led to drier and hotter conditions, putting forests and communities at risk, it’s the overwhelming fuel loads on the ground that put “the bullet in the gun,” says Will Harling, a fisheries biologist and restoration director of the Mid Klamath Watershed Council. In mixed-conifer environments such as Tuolumne County, the proliferation of small, shade-tolerant cedar—once cleared by Indigenous burners and natural ignitions—can be detrimental to larger trees, such as oaks, that serve as important food sources, with repercussions for humans and wildlife alike.

“There are just more trees in the Sierra Nevada than there have been historically for thousands and thousands of years,” Stephanie Pincetl, a professor and founding director of the California Center for Sustainable Communities at UCLA, explains in a 2020 video series on wildfires. She goes on to describe the consequences: “You’d get more groundwater recharge if you had less trees. You’d get more streamflow if you had less trees. You’d get less fire if you had less trees.”

Small trees take up water that becomes more precious in drought years, leaving larger trees prone to disease and to the invasive bark beetles that threaten native buckeye and tanoak. Recent research has shown a correlation between beetle infestations and fire severity. A 2023 study published in Fire Ecology found that concurrent drought and bark beetle infestation could affect fuel on the ground and in the canopy, with the “potential to lead to heavy and dry fuel loads that under certain weather conditions may result in more extreme fire behavior and severe effects.” In other words, a lack of prescribed burning leads to bigger wildfires.

An overabundance of smaller trees leaves less water flowing into the Klamath and other regional rivers, in turn threatening the spring and fall runs of native Chinook and coho salmon. Healthy base flows are necessary to sustain juvenile coho, which typically become stressed at river temperatures above 65 degrees F. “Restoring the fire process is crucial for restoring our salmon runs,” Harling says.

The repercussions pile on from there. Heavy rainfall following a wildfire can lead to flash floods, as when the 2022 McKinney Fire in Klamath National Forest caused a mass kill-off of fish along 50 miles of the Klamath River. On the flip side, flash-flood conditions are less extreme in a system managed with fire, Harling says: “Beneficial fire gave us those Goldilocks conditions where salmon could flourish.”

When wildfires take hold in areas that haven’t seen burns, the smoke can alter the trajectory of migratory birds. A U.S. Geological Survey-led study of tule geese published in 2021 in The Scientific Naturalist found that wildfire smoke concentrations led to geese “either stopping migration or altering direction and/or altitude of flights,” which authors said could play out to damaging effects: “Energy deficits such as we describe, especially when occurring in the context of incomplete knowledge of available food resource locations, can lead to increased mortality or reproductive rates insufficient to maintain goose populations.”

Land-use experts point out that smoke from wildfires is more toxic than that of controlled burns, releasing more health-harming pollutants. “We know fire emits a lot of CO2, so you really don’t want to be encouraging a forest health that will have lots of big fires,” Pincetl says. “Controlled burning is another matter: They’re low brush fires, and they don’t emit as much CO2 as these big conflagrations.” That said, experts stress that everyone—especially those with health concerns—should limit exposure to any type of fire smoke.

In addition to mitigating megafires and their repercussions, controlled burns can benefit wildlife. Since reimplementing cultural burns, Robbins says there has been a resurgence of black-tailed deer in her town of Weitchpec, allowing more hunts to resume on the Yurok Reservation. A 2022 study from the Karuk-UC Berkeley Collaborative found that prescribed burns employing Indigenous stewardship practices, or Traditional Ecological Knowledge, had a positive impact on elk habitat in the areas examined. Preston says that since the Karuk have increased burns, she and colleagues have seen anecdotal evidence of more elk: hoof prints in ash and surveillance photos of elk resting in burn sites. “That’s one of the really cool interactions I’ve seen with animals and fire—elk moving around in the burned areas afterwards,” she says.

That’s not to suggest controlled burns are without risk. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, over 99 percent of prescribed burns conducted by USFS go as planned, but escaped fires have resulted in tragic deaths and property damage, as occurred in the Santa Fe National Forest in New Mexico in 2022. Still, there is consensus the benefits outweigh the dangers where prescribed burns are appropriate.

In most cases, that doesn’t include cities. In greater Los Angeles, home to some 18.5 million people compared to Weitchpec’s 112, there are more human demands to balance against ecological threats, explains Howard Penn, executive director of the Planning and Conservation League, a National Wildlife Federation affiliate. In addition to more suburban and exurban sprawl pushing up against the Santa Monica Mountains, the chaparral ecosystem of Southern California differs from the state’s northern forests. Similarly, controlled-burn regulations are more complex with a more concentrated population. CAL FIRE requires burn permits year-round in 10 counties that make up Southern California, including Los Angeles and San Diego counties.

“Prescribed burns can still be used strategically in those applications in Southern California, but you have much more constraints than you do up here,” says Penn, whose organization is based in Sacramento. While forests tend to burn less frequently under good-fire management, chaparral likely burns more often due to human-caused ignitions and the spread of invasive plants. Most experts say neither controlled burns nor brush clearing would have prevented the Los Angeles fires.

“The air quality concerns get to be really, really big, as well as the risk of real damage to structures and lives if the [prescribed] fire escapes,” says Darrel Jenerette, a biology professor and landscape ecologist at University of California, Riverside. “This is a powerful way of reducing wildfire risks, but the trade-offs are really challenging to overcome.”

Wildfires following decades of fire exclusion can leave riparian zones—such as that surrounding Vesa Creek, a tributary of the Klamath River, pictured after California’s 2022 McKinney Fire—scorched and bald, which in turn can lead to flash flooding. A Chinook salmon (below) hides amid a curtain of bubbles in Northern California’s North Fork Salmon River. Above the water’s surface, the burn scar from 2014’s July Complex Fire extends down to the shoreline.

A grassroots solution

The state’s rural areas, however, have seen increasing interest in prescribed burns, such as the Twain Harte burn in April and another the same month farther north in Placer County.

“There’s a huge appetite from people to learn how to do prescribed fire, in the Sierra at least,” says Kocher of the Cooperative Extension Central Sierra. “People understand how important it is.” As landowners hear about the benefits of planned burns, there’s also a heightened need for education and coordination. That’s where the state’s growing network of prescribed burn associations, or PBAs, comes in. Quinn-Davidson of the UC Fire Network helped establish the state’s first PBA in Humboldt County in 2018. Today 27 PBAs cover about half of the state’s counties.

“Landowners are the experts on that piece of land that they own,” Kocher says. “They’re the ones who understand the history of the property, and they have the goals.”

While landowners set their own goals, PBA burns are regulated: They must occur roughly November to April, outside of fire season, and must comply with rules set by CAL FIRE and local air quality emissions districts. Some burns—those low in complexity or, as in Tuolumne County, under 2 acres—may not require a permit, but all burns require a burn plan to demonstrate due diligence, helping protect private burners from fire suppression costs if a prescribed burn does get out of control. Plans describe the area to be burned, noting power lines, road and water access and neighboring properties. A plan also details the removal of built-up litter and foliage that could keep an out-of-control fire raging, and it may establish buffer zones around buildings. A CAL FIRE-certified burn boss must approve the plan and may be on-site during a burn.

And then there’s good judgment. At the Twain Harte burn, Adam Dragland, a member of the Tuolumne County PBA steering committee who works in software and has firefighter training, reminded the group of a tenet of prescribed burning: “To burn or not to burn, that is the question.” Just because a permit has been issued doesn’t mean a burn should proceed. Landowners should assess day-of conditions, like temperature, wind and relative humidity. If those no longer align with a safe burn, it’s OK to reassess, postpone or cancel.

“What’s so cool about California is the ecosystem shift, which means the prescriptions shift too,” says Cordi Craig, who works for the Placer Resource Conservation District and leads the Placer PBA. A certified burn boss, Craig specializes in the mixed-conifer ecosystems of Placer County. “People get in their region, and then they become really good at burning within that region,” she says of PBAs prioritizing place-specific ecological and community needs.

But all good fire—whether in the mixed conifers of Northern California or other ecosystems in need of restoration, such as the oak forests of the U.S. Southeast—require sufficient funding and scientific data. The future availability of those resources is currently uncertain, with federal funding cuts slashing staff, personal protection equipment and research, and agency reorganizations jeopardizing federal agencies’ ability to conduct burns or follow through on commitments to Tribal and other regional partners.

“One of my favorite things about the PBA movement is really that local flavor,” Quinn-Davidson says. “It’s so grassroots, which is so important, because prescribed fire and the use of fire, in general, is very versatile. It’s definitely a unifying force. And, gosh, we could use as many of those as we can get in this current day.”

NWF priority

Restoring Relationships

The National Wildlife Federation is committed to Indigenous stewardship. Learn more about the Tribal and Indigenous Partnerships Enhancement Strategy. NWF also supports place-based conservation through initiatives including the Southeast Forestry Program, restoring fire to iconic longleaf pine forests.

Read about writer Kate Gonzales.

More from National Wildlife magazine and the National Wildlife Federation:

Undaunted, Grad Students Return to the Field After Wildfires »

Make Your Garden Fire Smart & Wildlife Friendly »

Blog: Using Fire to Fight Fire »