40-Plus States Submit Wildlife Action Plans This Fall. Here's What That Means.

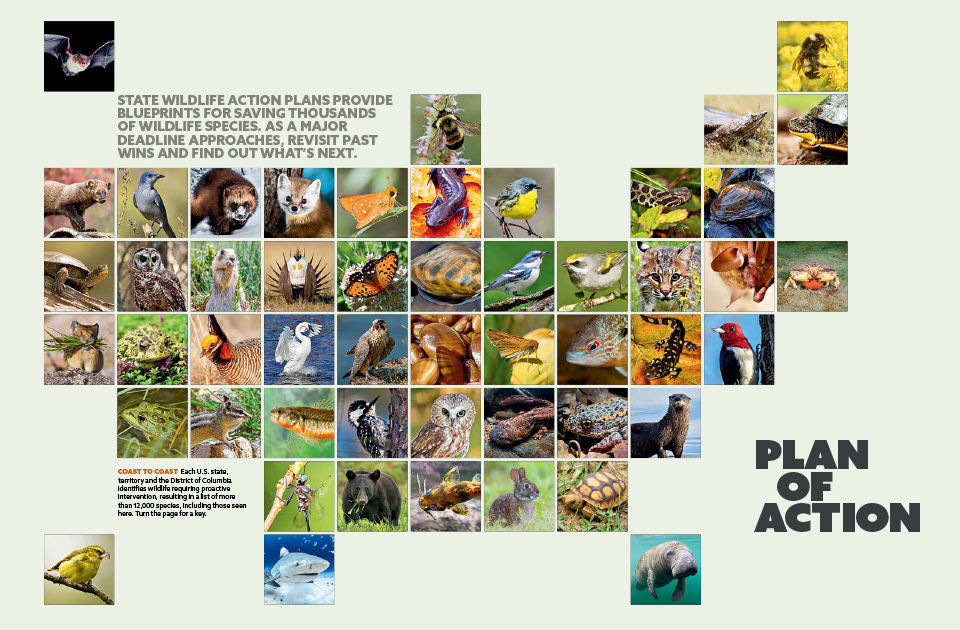

State wildlife action plans provide blueprints for conserving thousands of wildlife species. As a major deadline approaches, revisit past wins and find out what's next.

- By Delaney McPherson

- Conservation

- Sep 24, 2025

Each U.S. state, territory and the District of Columbia identifies wildlife requiring proactive intervention, resulting in a list of more than 12,000 species, including those seen above. See map key and credits at end of article.

ONE OF THE FIRST SPECIES LISTED under the U.S. Endangered Species Act of 1973, the Kirtland’s warbler was down to 167 breeding pairs by 1974. Found only in parts of Michigan, Wisconsin and Canada, the warbler was in dire straits.

In 2005, the inaugural Michigan Wildlife Action Plan listed the Kirtland’s warbler as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need, and in 2008, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources began using State Wildlife Grants to support the bird’s recovery: replacing trees too old to shelter bird nests, planting new pines and monitoring native cowbird populations to ensure they didn’t outcompete the warblers. The grants also helped fund regular censuses monitoring warbler populations and tracking the species’ progress.

“One thing that’s really cool about the wildlife action plan is that we essentially met all of the goals listed for Kirtland’s warbler for the decade,” says Erin Victory, a wildlife biologist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. “[The action plan] provides the mechanism for collaboration and funding, which has been critical to support this whole operation.”

The warbler was delisted in 2019, and by 2021 it had rebounded to roughly 2,245 breeding pairs—a testimony to the meaningful change state wildlife action plans and the associated funding can produce. And yet these tools are at risk.

PICKY NESTERS Kirtland’s warblers (pictured, held by a scientist) only nest on the ground beneath the cover of low branches of the jack pine tree. If a tree is too old and the boughs too high, it’s a no-go.

“[Warblers prefer] jack pine between the ages of 5 and 20. Once they get to that age, the branches get too high.” –Erin Victory

Committing to conservation

U.S. Congress created State Wildlife Grants in 2000—and expanded the program to include Tribal Wildlife Grants the following year—to direct federal funds toward crucial state wildlife conservation efforts. Those moves represented the culmination of decades of collaborative efforts by groups including the National Wildlife Federation to secure dedicated federal funding for wildlife. To determine how that money, typically $70 to $90 million a year, will be allocated, Congress mandated in 2000 that every U.S. state, territory and the District of Columbia draft and submit a state wildlife action plan by fall 2005.

“Before [the plans’] creation, people were doing a lot of good work, but it was ad hoc and depended on what we knew at the time on what species might be in trouble,” says Naomi Edelson. Now senior director of wildlife partnerships for NWF, Edelson led the Teaming with Wildlife coalition that helped secure funding and supported the first generation of action plans for the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies, a national nonprofit.

State wildlife agencies draft the plans, often in partnership with scientists and other conservation experts, and include feedback from the public. The plans pinpoint which wildlife species in each state or territory require proactive intervention—known as Species of Greatest Conservation Need—and identify the species’ habitats; key threats they face; intended conservation actions; strategies for monitoring the species, as well as for reviewing and updating those approaches; and opportunities for public input. The plans must be revised at least every 10 years, with the first revision having taken place in 2015, and the next iteration from more than 40 states and territories due October 1 of this year. (A handful submitted early.)

“In some states, over 10,000 hours go into these plans,” says Mark Humpert, director of conservation initiatives for the Association of Fish & Wildlife agencies, citing the need for accurate species and habitat data and ample time for public input. “States with a lot of people or large geographies take a lot of time to do the outreach. ... [The plans have] only gotten better as the science has gotten better.”

Once a state submits its plan, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service either will request additional information or approve it—a process that generally takes six months to a year. In turn, all requests for grant funding must align with a project outlined in the state’s action plan and must involve a Species of Greatest Conservation Need.

The goal is not only to help recover wildlife already listed under the Endangered Species Act but to take proactive steps before other species’ population sizes and habitats severely decline. To date, the action plans have identified more than 12,000 Species of Greatest Conservation Need—from pygmy rabbits in the western United States to red-cockaded woodpeckers in the Southeast, regal fritillary butterflies in the Midwest and Micronesian geckos in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands—as well as a multitude of strategies to support them.

COMING HOME Canadian wolverine populations have naturally recolonized parts of Idaho, Washington, Oregon and Montana, supported by the active conservation of prey species and bans on trapping and poisoning.

“What makes [wolverines] susceptible to exploitation is they occur in low densities. In Idaho, there is room for 120 animals.” –Cory Mosby

Crossing state lines

The plans also allow states to identify areas where they might work together to benefit wildlife. In the Northwest alone, Idaho, Montana, Washington and Wyoming all list the North American wolverine as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Wolverines were extirpated from the Lower 48 in the 1930s due to trapping, loss of prey and secondary poisoning meant for larger animals such as wolves and grizzly bears. Although wolverines have returned to parts of the northwestern United States from Canada since then, the populations are not genetically distinct and getting accurate data on the elusive species still proves difficult.

“Thinking about this species on a state-by-state level is not applicable, because it’s so low density and wide ranging,” says Cory Mosby, coordinator of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game’s large carnivore program. “You have to think of it as a multistate unit before you have a large enough population to make sense.”

With that approach in mind, the four states’ wildlife agencies joined with partners including the Northern Arapaho Tribe, the Eastern Shoshone Tribe and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes to form the Western States Wolverine Conservation Project in 2016. Using nearly $200,000 in competitive State Wildlife Grants, in addition to funds from the states and private organizations, the group conducted the first large-scale survey of wolverines in the region, gathering data that ultimately helped inform the decision to list the species as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2023.

NWF affiliate Conservation Northwest helped train volunteers who conducted the survey, leading to a robust carnivore monitoring program in Washington. “We were able to provide support, and many of those volunteers became longtime camera maintenance folks,” says Laurel Baum, the organization’s Central Cascades watershed manager.

Another collaborative effort occurred in the Northeast, where state biologists from Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York and Pennsylvania formed the Northeast Blanding’s Turtle Working Group in 2004.

“Turtles in particular are very susceptible to population reduction because of their life history,” says John Kanter, co-founder of the working group and now a senior wildlife biologist with NWF. “They’re 15 years old before they can reproduce, so they have to survive 15 years—and very few do. They were very high priority among reptiles in the region, so we put the information together from the individual state plans into a regional assessment.”

When all five states identified the Blanding’s turtle as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need in their 2005 action plans, they received and used State Wildlife Grants to fund regional monitoring efforts: assigning priority protection areas and creating signage and artificial nests. The project served as a blueprint for subsequent northeastern working groups on wood turtles, spotted turtles, bog turtles and eastern box turtles.

While Indigenous groups do not submit their own plans, they independently manage their natural resources and use tools including the Tribal Wildlife Grants program. Many Tribal priorities overlap with those of state partners, and in the end, wildlife benefit, as was the case with the Red Lake Band of Chippewa and lake sturgeon. The sturgeon had been extirpated in Minnesota’s Red Lakes since the 1950s due to overexploitation and dam construction. But in 2007, the Red Lake Band began using Tribal Wildlife Grants to reintroduce the fish. In the more than 15 years since, the Band has continued to use grant funding to regularly stock the lakes—especially important as the fish don’t begin reproducing until they reach age 20 or so.

“Lake sturgeon don’t spawn every year. There can be two to three years in between,” says Pat Brown, fisheries director with the Red Lake Department of Natural Resources. “We need a wide variety of ages, and that’s where we’re at now.”

Brown estimates the current sturgeon population in the lakes is around 140,000. The Band plans to continue stocking through 2029, at which point the population should be self-sustaining. The sturgeon’s recovery in the Red Lakes has been bolstered by additional stocking and water quality improvement projects in the watershed conducted by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources—which has identified the sturgeon as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need since its 2005 action plan—and the White Earth Band of Chippewa. These combined efforts, along with dam removals, now allow the sturgeon to freely flow from the Red Lake River into the lakes and back again.

The future of the funds

To determine how much money a given state will receive each year, Congress uses a formula based on human population and total land area. While state wildlife action plans are drafted every 10 years, Congress appropriates State Wildlife Grants annually. That means projects are continually at risk of defunding—a precarious position in the best of times.

Under the Trump administration, with many budgets getting cut and grants rescinded, that uncertainty is amplified. Earlier this year, the president proposed a budget that would zero out the grant program. Fortunately, strong bipartisan support resulted in the funds being reinstated as of summer 2025, but there is still work to be done to ensure the program remains. While some wildlife conservationists are betting that future grants won’t be canceled outright, others say it’s too early to discount the possibility.

“The plans aren’t going away [if the grants are cut], but capacity will be diminished,” Humpert says. “There are grave concerns that if this funding goes away, the programs will be a shell of what they used to be.”

Most action plan projects are not wholly funded by the grants but rather a mix of federal, state and nonprofit dollars. If the grants are terminated, the efforts may continue, but it’s worth noting that many grant-making states and nonprofits, including NWF, receive and redistribute federal support whose outlook is currently under fire.

In a best-case scenario, Congress could fund State and Tribal Wildlife Grants in perpetuity to achieve the plans’ goals. In 2016, the Blue Ribbon Panel on Sustaining America’s Diverse Fish and Wildlife Resources determined it would take $1.3 billion to implement all initiatives in the 2005 wildlife action plans. While a total estimate for the 2025 plans won’t be available for some time, the 2025 plans and all future revisions could be permanently secured if Congress passes the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, a major NWF initiative. See “NWF priority,” bottom, for more.

Even without dedicated funding, the plans provide vital information—population sizes, habitat quality, conservation tactics and opportunities for public engagement—necessary to protect and recover the thousands of Species of Greatest Conservation Need already identified.

“We now know so much about what we need to do,” Edelson says. “We have the action. We just need the resources to get it done.”

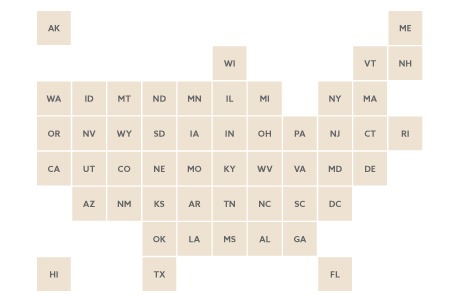

WHO'S IN YOUR STATE?

This map represents a sampling of the thousands of species listed in wildlife action plans. While not pictured on the map, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands also identify and submit Species of Greatest Conservation Need.

Alabama (AL) Marsh rabbit Alaska (AK) Little brown bat Arizona (AZ) Chiricahua leopard frog Arkansas (AR) Red-cockaded woodpecker California (CA) American pika Colorado (CO) Lesser prairie-chicken Connecticut (CT) Tricolored bat Delaware (DE) Red-headed woodpecker District of Columbia (DC) Northern river otter Florida (FL) West Indian manatee Georgia (GA) Gopher tortoise Hawai‘i (HI) Kiwikiu or Maui parrotbill Idaho (ID) Pinyon jay Illinois (IL) Jefferson salamander Indiana (IN) Clubshell Iowa (IA) Regal fritillary Kansas (KS) Arkansas darter Kentucky (KY) Pink mucket Louisiana (LA) Louisiana black bear Maine (ME) Yellow-banded bumble bee Maryland (MD) Eastern tiger salamander Massachusetts (MA) Brook floater Michigan (MI) Kirtland’s warbler Minnesota (MN) Leonard’s skipper Mississippi (MS) Frecklebelly madtom Missouri (MO) Peregrine falcon Montana (MT) Wolverine Nebraska (NE) Trumpeter swan Nevada (NV) California spotted owl New Hampshire (NH) Blanding’s turtle New Jersey (NJ) Bobcat New Mexico (NM) Peñasco least chipmunk New York (NY) Eastern massasauga North Carolina (NC) Eastern hellbender North Dakota (ND) American marten Ohio (OH) Cerulean warbler Oklahoma (OK) Ozark emerald Oregon (OR) Western pond turtle Pennsylvania (PA) Golden-winged warbler Rhode Island (RI) Jonah crab South Carolina (SC) Gopher frog South Dakota (SD) Greater sage-grouse Tennessee (TN) Northern saw-whet owl Texas (TX) Bull shark Utah (UT) Boreal toad Vermont (VT) Spiny softshell turtle Virginia (VA) Longear sunfish Washington (WA) Fisher West Virginia (WV) Two-spotted skipper Wisconsin (WI) Rusty patched bumble bee Wyoming (WY) White-tailed prairie dog.

OPENER CREDITS: AL: DONALD M. JONES (MINDEN PICTURES); AK: MCDONALD WILDLIFE PHOTOGRAPHY INC. (THE IMAGE BANK/GETTY IMAGES); AZ: STEVEBYLAND (ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES); AR: RENEE BODINE (USFWS); CA: SHATTIL & ROZINSKI (NATURE PICTURE LIBRARY); CO: NATTAPONG ASSALEE (ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES); CT: PETE PATTAVINA (USFWS); DE: MARVINANN PATTERSON (USFWS); DC: TOM KOERNER (USFWS); FL: BRENT DURAND (MOMENT/GETTY IMAGES); GA: RANDY BROWNING (USFWS); HI: RYAN WAGNER; ID: GLENN BARTLEY (BIA/MINDEN PICTURES); IL: S & D & K MASLOWSKI (IMAGEBROKER/ALAMY); IN: RYAN HAGERTY (USFWS); IA: JILL HAUKOS (KONZA PRAIRIE BIOLOGICAL STATION); KS: DANIEL FENNEL (USFWS); KY: MONTE MCGREGOR; LA: CLINT TURNAGE (US DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE); ME: THOMAS WOOD; MD: BARRY MANSELL (NATURE PICTURE LIBRARY); MA: RYAN HAGERTY (USFWS); MI: PCHOUI (ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES); MN: RICK & NORA BOWERS (ALAMY); MS: BRETT ALBANESE (GDNR); MO: JILL BEIM; MT: ROB G. GREEN; NE: STEVE DEGENHARDT (USFWS); NV: RICK KUYPER (USFWS); NH: PATRICK RANDALL; NJ: GRAYSON SMITH (USFWS); NM: JIM STUART (NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF GAME AND FISH); NY: NATHAN RATHBUN (USFWS); NC: ISAAC SZABO (ENGBRETSON UNDERWATER PHOTOGRAPHY); ND: RT IMAGES (SHUTTERSTOCK); OH: PS50ACE (ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES); OK: DAYBREAK IMAGERY (ALAMY); OR: SEKARB (ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES); PA: BRIAN E SMALL (NATURE PHOTOGRAPHERS LTD/ALAMY); RI: ANDREW J. MARTINEZ (BLUE PLANET ARCHIVE/ALAMY); SC: JAMES LYON (USFWS); SD: JARED LLOYD (MOMENT/GETTY IMAGES); TN: GERALD CORSI (E+/GETTY IMAGES); TX: HENLEY SPIERS (NATURE PICTURE LIBRARY); UT: ANNA RICHARD (ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES); VT: QUINN KEON (ALAMY); VA: RYAN HAGERTY (USFWS); WA: LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDT (ALAMY); WV: ANDY BIRKEY (ALAMY); WI: DAWN MARSH (USFWS); WY: GERALD DEBOER (ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES)

NWF priority

Funding the Work

The Recovering America’s Wildlife Act would provide up to $1.4 billion annually to implement state wildlife action plans and include an historic investment in Tribal fish and wildlife management. NWF currently is working with the bill’s bipartisan sponsors on its introduction to the 119th U.S. Congress. Learn more.

Read about Delaney McPherson.

More from National Wildlife magazine and the National Wildlife Federation:

The Endangered Species Act at 50 & What’s Next for Wildlife »

Are Entomologists as Endangered as the Insects They Study? »

Blog: 7 Ways State Wildlife Action Plans Save Species »